So what happened? Unfortunately, the impervious clay on which it rested and which allowed the shallow basin in which it nestled to fill with water was of a very particular kind. This 'attapulgus' clay had some special characteristics which made it suitable for making 'Fuller's Earth' (valued in several industrial processes). So it was that, in 1976, a large clay-pit mining this mineral was opened next to the laguna. It was to produce that absolutely vital material …. cat litter! What inevitably followed has been rightly described as an ‘ecological disaster’. The deep excavations of the pit altered the hydrology of the basin reducing the water level in the laguna and reducing the persistence of winter flooding. Eventually, the pits and the waste they produced swallowed up about a third of the original laguna. Unfortunately, despite its rich avifauna, the laguna lacked the sort of legal protection for environmentally important sites that we'd take for granted these days. With its supply of water compromised things looked set to go into a terminal decline as the basin dried out (see - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17Krs9rhPTo).

Fortunately, although commercial interests could ignore protests, they couldn't win in the courts and in 1998 they lost a crucial legal case. This forced the mining consortium to abandon the site although they were not compelled to restore the habitat as many had hoped. With the area now under the control of the Junta de Andalucia, an ambitious plan to restore the habitat was launched. That much maligned organisation, the EU stumped up over €3 million and the Andalucian junta added nearly €5 million. Work to solve the hydrological problems began in September 2010 and work to seal the old clay-pits should finish this year (2014). With the active engagement of local people the laguna has been fenced off, trees have been planted and an educational programme launched. It's not been without difficulties and even as late as 2004, when the reserve's boundaries were settled, there were problems of damage from agriculture and illegal dumping.

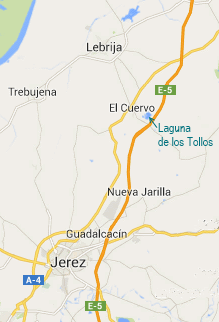

Laguna de los Tollos - May 2011

Laguna de los Tollos - May 2011 On my first visit in early April this year (2014) I found the place alive with birds once more, but, significantly, the high water levels were no longer simply a matter of fortuitous winter rain, but of careful planned management. The birds included Purple Gallinule, over 30 Black-necked Grebes, half a dozen Flamingos, similar numbers of Spoonbill, a good variety of ducks (Pochard, Red-crested Pochard, Gadwall, Shoveller & Mallard), a couple of dozen Whiskered and a few Gull-billed Terns, Avocets, Black-winged Stilts, Little Ringed Plovers, Collared Pratincoles and in excess of 300 Coots (perhaps a hopeful sign that Crested Coot may soon return). A subsequent visit in early May produced similar range of species plus several passing Curlew and Common Sandpipers and, best of all, 3-4 White-headed Ducks. Some eight birds are present this summer and hopes are high that they may soon breed once more. Other birds present on the reserve this spring include Purple Heron, Little Bittern, Great-reed and Melodious Warblers. Later in the season the tamarisks here should also be worth checking for Olivaceous Warblers. Black-winged Kite are present nearby and during passage almost anything might turn up. I certainly found much more of interest on my two visits to Laguna de los Tollos this year than I managed to find at Laguna de Medina, a much better known and more highly regarded site.

Education work at Laguna de los Tollos

Education work at Laguna de los Tollos  Laguna de los Tollos

Laguna de los Tollos

RSS Feed

RSS Feed