Ojen Valley - photo taken when access was unrestricted!

Ojen Valley - photo taken when access was unrestricted!

| Birding Cadiz Province |

|

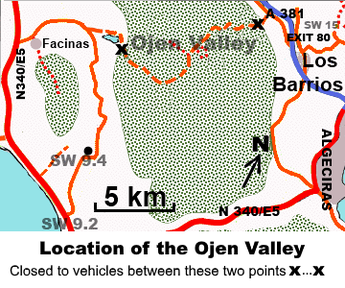

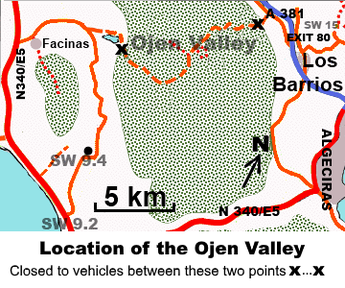

Ojen Valley - photo taken when access was unrestricted! Ojen Valley - photo taken when access was unrestricted! As I've reported elsewhere on this blog (see - http://birdingcadizprovince.weebly.com/cadiz-birding-blog-page/ojen-valley-access-denied) despite being used by birders for decades the Ojen Valley road is no longer open to vehicles although you can still walk or cycle along the 16km track. This, however, is not a practical proposition for most visiting birders who neither have a bicycle nor the resources to be picked up at the far end of the walk. The site is still noted in Cadiz Tourismo's recent 'Birding Cadiz' booklet (yes, they nicked my title) with the warning that “You need special permission to access the road with a vehicle” but, with a genius so often typical of such publications, doesn't tell you either to whom to apply or the criteria the authorities use to grant permission! What seems like a no-brainer to me evidently isn't so evident to them.  I'm very grateful, therefore, to Fraser Simpson (a regular visitor to the area) for the following information. Apparently you need to submit a form entitled “Modelo Petición de Autorizaciones Actividades de uso Público, Turismo Rural y Turismo Activo” which is available fro the Natural Parks section of the Junta de Andalucia. This form also seems to be available online at http://www.famp.es/famp/intranet/documentos/rio_palmones/9.%20Modelo%20solicitud%20autorizacion%20actividades%20UP.pdf (although this example refers to the Rio Palmones in the webaddress, I think that it's a standard form). I have also reproduced it at the end of this post but I suggest people check online rather than rely on the forms reporduced here. Applicants must send the signed and completed form by e-mail to [email protected] addressed to the Director Conservador del Parque Natural Park. Those with good Spanish could try phoning the park headquarters on +34 856 58 75 08 856587508 or write a letter to Parque Natural de los Alcornocales, 11180 Alcalá de los Gazules, Cádiz, Spain. It might also be worth calling at the offices of the Parque Alcornocales in person (it's situated just off the A 381 next to the information centre on the Benalup road below Alcalá de los Gazules). I've had dealing with the staff when they were located in Alcalá and found them to be pleasant and helpful (although having only limited English). Fraser's permit was for a week and was granted without charge. However, he was visiting with group of university students and has been studying a site in the Ojen valley for some years so may have been at an advantage compared to 'ordinary' birders. Since I've mentioned him here, I'll also take the opportunity to strontgly recommend Fraser's superbly illustrated, detailed and very useful website. His trip report on his visit in spring 2017 (one of about a dozen on this area based at Zahara de los Atunes) which is well worth browsing (see - http://www.fssbirding.org.uk/costadelaluz2017trip.htm. His notes include sonograms, excellent sketch maps and a comprehensive species list.

0 Comments

Logo of Ebro Foods Logo of Ebro Foods Well into the twentieth century, the view persisted in Spain (and elsewhere), that marshes, lagoons and wetlands were, at best, unproductive spaces and, at worst, a reservoir for disease. Hence there was little or no opposition to draining them to convert them into farmland or using them as convenient places to dump waste (particularly from the sugar refining industry). Most notoriously, this attitude caused the loss of the iconic lake that was the Laguna de la Janda but what is less widely appreciated is that many other small, but valuable, lagunas were also lost during this period. Even the much celebrated Laguna de Medina was not immune and came perilously close to being converted into a reservoir in the mid 1950s. Perhaps, by persisting into the 1980s or even later, this negative attitude towards the environment lasted longer in Spain than elsewhere (particularly amongst politicians) but there are promising signs that the early decades of this century things have changed. Not that, as current threats to the Coto Donana and the sad tale of Laguna de Torrox (see below), remind us, there's any reason to be complacent but there are straws in the wind that wider societal attitudes are changing.  Ecologistas en Accion - a driving force for change Ecologistas en Accion - a driving force for change Several recent environmental projects in the province give cause to hope that in Spain there's now a greater regard for the environment and the importance of protecting unique environments than in the recent past. In large part, this change can be ascribed to pressure from goups like Ecologistas en Acción (Ecologists in Action). This confederation of over 300 groups, formed in 1998, is particularly strong in Andalucia which has over 100 groups. Exactly how far pressure from these groups has changed the political landscape is difficult to judge but there's no doubt that parading your 'ecological credentials' is now seen as excellent PR for large companies in a way which would have been quite alien a decade or two ago. To some extent, of course, legislation to protect the environment (and calls for more stringent laws) has forced their hand of large companies too. I've already written at length about the restoration of the Laguna de los Tollos (see here) but two further projects in the Jerez area give cause for cautious hope.  Slender-billed Gulls - a species that has benefited by the restoration of the Marismas de Mesas de Asta Slender-billed Gulls - a species that has benefited by the restoration of the Marismas de Mesas de Asta The first and by far the most significant is the transformation of the Marismas de Mesas de Asta (also called Haza de la Torre) just north of the city (see also my previous blog about this site here). Evidently, partly due to changes in EU rules (, the sugar factory at Guadalcacín factory (Cádiz) was forced to close in 2007. This meant that the 36 hectares (or 48 hectares in some accounts) then used as 'settling ponds' by the factory at Mesas de Asta were no longer needed. Although constructed on what was then agricultural land, this area had previously been a marshy arm of the Guadalquivir Estuary. Even before the facility closed, a colony of Collared Pratincole tried to establish itself in the area (2002) but productivity was limited by the presence of many rats and semi-feral dogs. So, instead of restoring farmland, it was decided to recreate the original marshland (although the cynic in me wonders whether this option might have been cheaper too!) The result has been little short of astonishing. The number of breeding pairs of birds has shot up from 99 in 2005 to 1,485 in 2011 after creation of the wetland and wintering birds in the same period rose from 1,243 to 4,912. The wetlands are now a significant site for wetland birds not merely for Cádiz but for the whole of Andalucia. Significant breeding species include Gull-billed Tern (1,000+ pairs, one of the largest colonies in Europe) and Slender-billed Gull (450 pairs, 40% of the Andalucian population) plus good populations of Avocet (250 pairs) and Black-winged Stilt (50 pairs). It is also a significant site for Marbled Teal. Less significant for conservation, but also of interest to birders, the site also attracts Marsh Harriers, Montagu's Harrier, Kentish Plover, Lapwing and a wide range of passing migrants – Osprey, Wood Sandpiper, Black-tailed Godwits, etc.  Marismas de Mesas de Asta Marismas de Mesas de Asta Having been achieved for the relatively modest sum of €1.5 million (€1.25 from Ebro Foods, who operated the facility, and the rest from local authorities) this must be regarded as money well spent. Not surprisingly, both the tourist boards for Jerez and Cádiz Province have started promoting this as a site for ornithological tourism. So far, so good. Unfortunately, despite being well promoted, in April 2017 visiting British birders were asked to leave the area (albeit very politely). The site of the former settling ponds have always been clearly fenced off but previously I and many others have been able to access the edge of the small lagoon here by following a clearly marked track (tricky to drive but easy to walk along) in the past. However, according a press report in 2013 ”The property, although private, is visitable upon request to the owners” (although it's not clear whether this applies to the whole area or just those parts north of the track beyond the padlocked gate). Naturally, despite searching the internet and asking local contacts, I've been unable to discover how access may legitimately be obtained since it's nowhere clear who it is you need to contact (an email to Ebro Foods went unanswered). Fortunately, all of the larger, more interesting species can be seen and identified (although a scope helps) if you park off the road near the locked gate and scan the area without walking to the lagoon. However, there's no doubt that for many smaller species (warblers, small waders, etc) this is entirely unsatisfactory. If the authorities are serious about promoting this superb site to birding tourists, then the situation must be clarified, access regularised and basic facilities provided. A couple of information boards and a viewing screen would be a cheap and quick solution for the small lagoon. Access to the larger wetland beyond the locked gate where the terns and gulls breed is more problematical but experience at Rye Harbour in Sussex (UK) shows that an active gull/tern colony can co-exist with managed low level tourism. Properly managed, this site could rapidly become very popular with visiting birdwatchers.  Location of Laguna de la Quinientas (screen grabs from GoogleEarth) Location of Laguna de la Quinientas (screen grabs from GoogleEarth) The second, much smaller, restoration is currently underway at Laguna de las Quinientas which is on the far side of the E-5 (AP-4) c3.5 km NW of Laguna de Medina. When I first returned to Andalucia a decade or so ago, I had distinct feelings of deja vu as I searched fruitlessly for this laguna (which was mentioned in my old copy of “Where to Watch Birds in Southern and Western Spain”). Over thirty years earlier, we had similar problems trying to find Laguna de La Janda which, sadly, was then still marked on our large scale road map. Not locating the Laguna de las Quinientas was equally excusable not merely because it's only 12 hectares in size but also since by that time it, like Mesas de Asta marsh, was a victim of the sugar industry having been used as a settling pond for a nearby sugar beet factory. This was particularly tragic as the site had previously been home to 17 species of bird including endangered species such as Crested Coot, White-headed Duck and Marbled Teal. To make matters worse, from the 1980s onwards the toxic sludge caused extraordinarily high wildfowl mortality figures (over two thousand birds alone in 2005 - 2011). Not surprisingly, this attracted the attention of Ecologistas en Acción. After some public pressure, in 2011 the sugar company changed its production methods so that only a three years later waterfowl mortality was reduced to zero. However, thanks to a build up of sludge the maximum depth of the laguna had been reduced to half a metre, instead of three, which meant it was far more prone to drying out. The remedial work required to remedy this by removing the sludge was funded, to the tune of €42,035, by the Ministry of Environment and is already proving beneficial. As yet, though, the vegetation has yet to grow to the extent that it can support its former range and number of birds.However, water polluted by agri-chemicals running into the laguna from nearby fields remains a problem. Partly in order to monitor this site, the Ecologistas en Acción have suggested that, when restored, the laguna should be accessible to the public (in part, this reflects current concerns that several lagunas in the province on private land may be being neglected) . Access shouldn't be an unsurmountable problem as there's a rough track running c1.5 km north to the site from just after where the CA 3109 goes under the E-5 just beyond the cement works.  Lagina de Torrox, Jerez (Wiki Commons) Lagina de Torrox, Jerez (Wiki Commons) Access, as long as it's controlled (which might be the rub in cash strapped Spain) and directed where necessary, should be no bolt-on afterthought since it is vital to involve the public in these schemes. At one level this is simply a matter of fairness where money from the public purse is involved but it's also a practical measure since it should allow easier monitoring and to impart a 'sense of ownership', both of which help to prevent further abuses from occuring. Rather than simply using such projects as a prop for companies to appear 'green', by exploiting ornithological tourism and promoting environmental education these sites have both a tangible and intangible 'value'. In this, the fate of the Laguna de Torrox serves as a pertinent warning. This small laguna on the outskirts of Jerez was once the haunt of Abel Chapman & Walter Buck (authors of the seminal Victorian book 'Wild Spain') has now been swallowed up a decade or so ago by a housing development and made into a 'feature'. However, the attractive lagoon encircled by a pleasant 'passeo' that the developers doubtless promoted, has become an enivironmental nightmare with polluted waters, dying fish and dumped rubbish. Perhaps it was simply too close to Jerez to be saved from urban sprawl but a more sympathetic approach preserving it as real 'green lung' may have saved it and given the city a real asset. Whilst recent developments as described here are hugely encouraging, any optimism should also be tempered by the fact that even a well know site like Laguna de Medina continues to suffer from the unintentional introduction of carp which have catastrophically disrupted the laguna's ecology to the disadvantage of nationally important bird species. This happened following extensive floods and the worry is that, even if the authorities remove the carp (as they did after a previous invasion), until the source of the fish is removed this could happen again. Elsewhere a lack of regular maintenance or real engagement with ornithological tourism is obvious. A number of sites could benefit from relatively simple (and not ruinously expensive) measures which could greatly help visitor accessibility (although as a foreigner I'm probably unaware of many of the problems - political, financial and practical - that prevent this). Perhaps, reflecting the availability of resources, the authorities seem better at providing glossy booklets and attending the UK Bird Fair (where the Andalucia stand is one of the largest and most generously manned) than taking practical steps. Further, whereas in the UK the statutary conservation bodies (Natural England et al) have embraced encouraging visitors, there sometimes seems to be more of a "them and us" attitude (as there once was in the UK) by the authorities in Spain. That's not to disparage the good work that's being done, the many great people working hard to improve things or the progress that has been made, but, in my impatience, at times it seems the authorities' lefthand has no idea what its righthand is doing. References:

Books & booklets: A series of articles on the excellent website www.entornoajerez.com/ about lagunas around Jerez are invaluable not least because they can be translated using the 'Google Translate' service. If your Spanish is up to it then download the excellent online booklet which collects these notes together at https://issuu.com/entornoajerez/docs/humedales . Wild Spain by Abel Chapman & Walter Buck - https://archive.org/details/wildspainrecords00chaprich Newspapers: www.diariodejerez.es/jerez/renacer-incubadora-natural_0_886412041.html www.diariodejerez.es/jerez/humedal-campina_0_704329825.html www.diariodejerez.es/jerez/Consistorio-Plan-Urban-recreativa-Torrox_0_635036664.html www.diariodesevilla.es/andalucia/Mal-peces-muertos-laguna-Jerez_0_942206190.html Ecologists in Action: www.ecologistasenaccion.org/article31578.html www.ecologistasenaccion.org/article6994.html |

About me ...Hi I'm John Cantelo. I've been birding seriously since the 1960s when I met up with some like minded folks (all of us are still birding!) at Taunton's School in Southampton. I have lived in Kent , where I taught History and Sociology, since the late 1970s. In that time I've served on the committees of both my local RSPB group and the county ornithological society (KOS). I have also worked as a part-time field teacher for the RSPB at Dungeness. Having retired I now spend as much time as possible in Alcala de los Gazules in SW Spain. When I'm not birding I edit books for the Crossbill Guides series. CategoriesArchives

May 2023

|