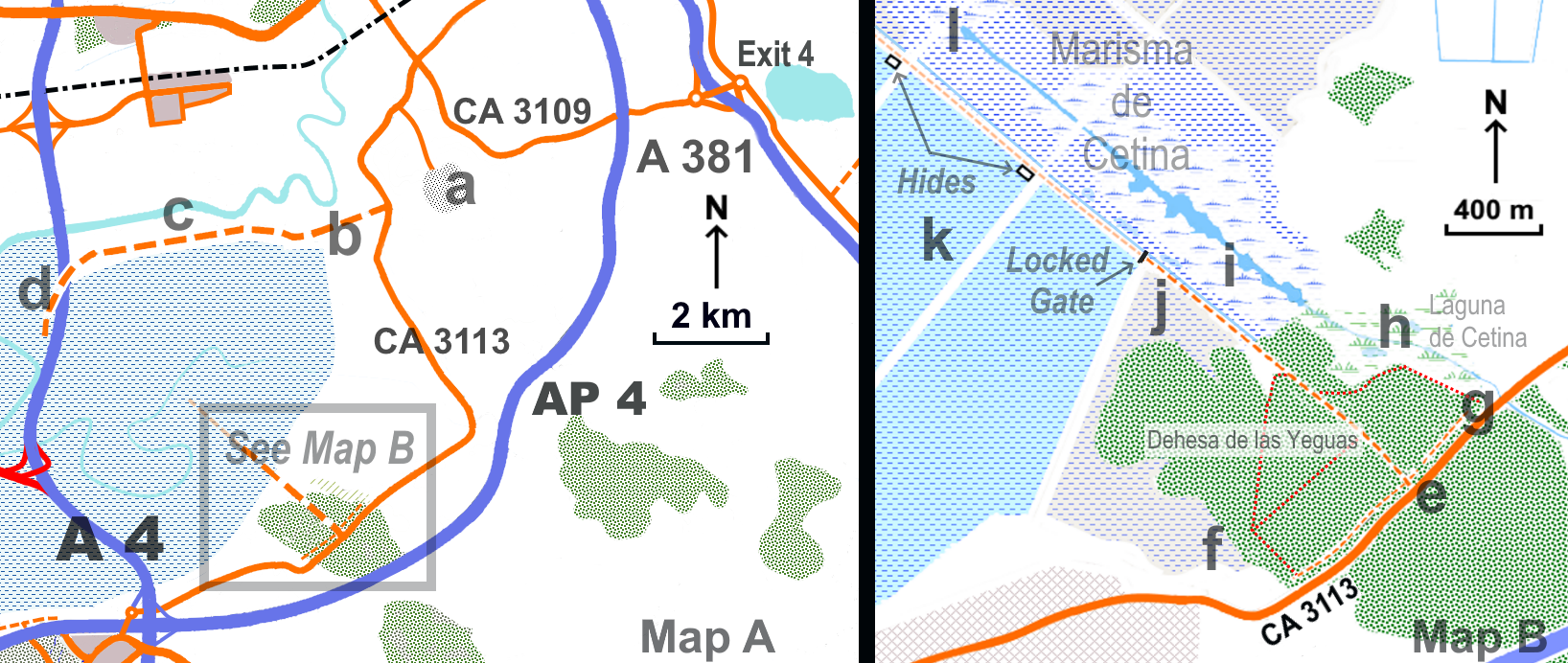

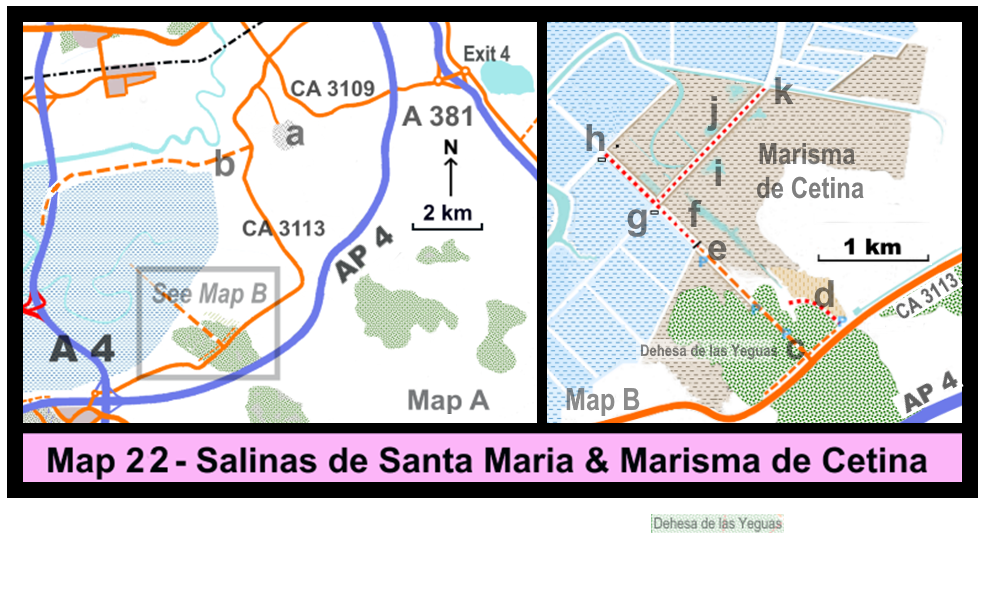

Salinas de Santa Maria from (d)

Salinas de Santa Maria from (d)

Old salinas from (f)

Old salinas from (f)  Looking back towards (i) from the gate

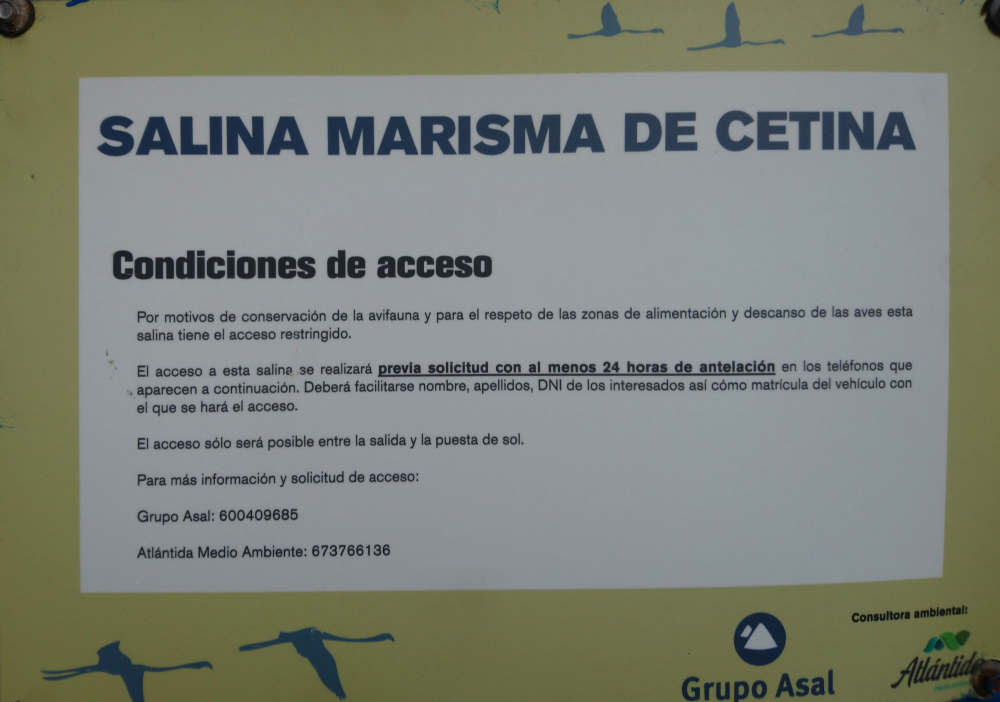

Looking back towards (i) from the gate  Notice with contact details for obtaining a permit

Notice with contact details for obtaining a permit Being the only relaible site for Savi's Warbler in the area (the nearest alternative being Brazo del Este in Seville Province) alone makes this an attractive destinantion for visiting birders in spring. If you obtain a permit (and even if you don't and only view from the track leading up to the gate) then the range of species here (waders, gulls, terns & larks) would nicely compliment a visit to Laguna de Medina (which less than 20 minutes away by car). It certainly has huge potential and simplified access would probably make this a three star site. A hidden gem?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed