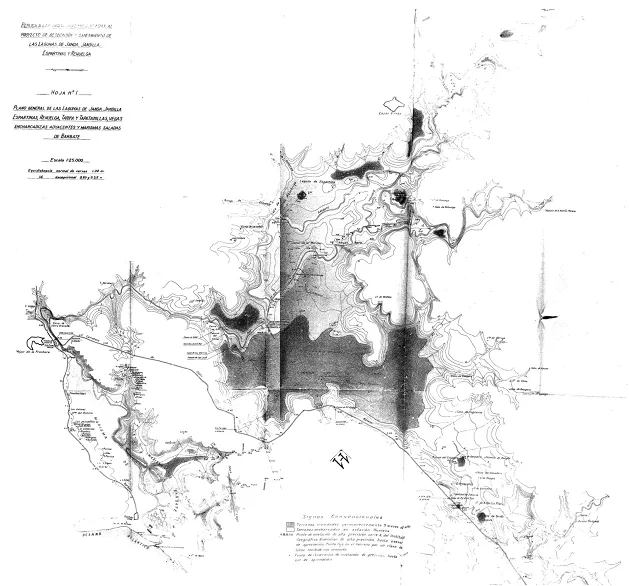

The Asociacion Amigos de la Laguna de la Janda's blog is always worth reading even if, for monoglots, like me it means doing so through the uncertain medium of Google Translate. Arguably, their latest post (see here) is their most significant one yet as it reports a recent finding regarding the legal status of La Janda. This legal paper (see here) has concluded that La Janda is publicly owned. This 38 page document probably doesn't make transparent reading even if you've perfect Spanish so my take on what it says and it's importance may well not be as accurate as it might be so read what follows with a pinch of salt! Fortunately, though, the document has an abstract in English which explains the background to the legal finding. This reads as follows: The opening In the second half of the 20th century, the largest wetland in Spain, the lagoon of La Janda (Cádiz), was drained, pursuant to a law that conferred special incentives to the drainage promoters such as ownership of the land. However, in the case of La Janda this drainage did not succeed and the Government reversed the grant of the property and announced its return to the public domain. Notwithstanding this, the Government has not exercised its jurisdiction to regain its full property rights, even though the Supreme Court has ruled in its favor and the land has retained its wetland characteristics. This paper analyzes the legal history of this event and the authority of the State for the restoration of the lagoon. The rest of the paper is not only in Spanish (of course!) but in a legal jargon that defeats online translation. However, from what I can make out (and what is suggested by the abstract) it seems that the failure to fully drain the land, as set out in the original grant, means that La Janda remains in public ownership. Not only that but in the paper's conclusions there's a relatively simple sentence which reads, in translation, as follows - "The investigation is not subject to the administration's discretion, but is a duty that must be fulfilled in the defence of its assets, in the face of which there is no scope for administrative inactivity". This I understand to mean that the governmental department responsible is legally obliged to take control of La Janda as it forms part of the state's assets. There's a good deal of dense legal argument (I think!) in the document but from what Google and my meagre Spanish can make out, the conclusion is that the restoration of the laguna, or at least of some of the wetlands, would be the in the public good and that therefore the administration is obliged to take action. At this point a note of caution must be added since those who currently farm La Janda are both very wealthy and well connected politically. One apparent example of this influence is that when, a few years ago, a paper was prepared on La Janda for a conference in Jerez on Spain's wetlands, it was suddenly pulled, without explanation, by the organisers. Talking to my well informed Spanish friends at the Birdfair last week, they seemed to be confident that the case is watertight(!), that the administration includes those willing to push this forwards and that the judgement can be used to exert pressure on those who farm the land to make concessions. That said, there also seemed an awareness that a wholesale restoration and any consequent loss of jobs was not feasible in the current climate (nearby Benalup has one of the highest unemployment rates in Spain). However, there seemed to be a real confidence that birding visitors should see concessions to allow for the wider public use of the area within a year or two. This may take the form of access along currently closed tracks to areas of wetland and of other interest (although whether this would be by permit or entirely open remains to be seen). In the longer term there may even be some restoration. It would be foolish to underestimate the reality of political inertia, the lack of funds for any significant restoration and the power of vested interests, but the judgement gives hope that this superb birding site may become still better in the foreseeable future. Watch this space .... Update - I am indebted to my friend Javi Elorriaga for the link to an article in La Vanguardia (see here) which, even in Google Translate, explains the situation very clearly. For those with good Spanish, he also directed me to a book on the restoration of La Janda (Bases ecologicas para la restauracion de los humedales de la Janda - Cadiz, España € 17.00 by Manuel Angel Dueñas López € 17.00 - see here)

1 Comment

Look at a large scale map of any part of Andalucia (and most of Spain come to that) and you will quickly discover that rural areas are crisscrossed by cañadas (droveways). Andalucia has a disproportionately high proportion of these old cattle trails - 3,000 km - amounting to 25% of the total national network. Their abundance reminds us of the former importance of transhumance (the seasonal movement of livestock) and that, before mechanisation, droving (herding animals along what amount to linear pastures) was the only way to get sheep and cattle to market. Hence these ancient vias pecunaira (as they are also known) are flanked by broad margins to provide grazing en route, wells to provide water (abrevaderos), overnight resting places (descansaderos or majadas) and points where counting animals to enable royal taxation was facilitated (puertos reales). Exactly how old these routes are is a matter of some dispute. Most authors suggest that they date to the early Medieval period but some suggest, perhaps fancifully, that they may be traced back far further into antiquity and are an echo of the migratory routes taken by wild animals and early human hunters who pursued them in Neolithic times. It is certain, though, that their use and legal status can be traced back to the 13th century. The most significant regulation was enacted by Alfonso the Wise of Castille in 1273. Their legal status as protected common land has since been confirmed and regulated by national laws in 1995 and local regulation in Andalucia in 2001. These laws were enacted to ensure the conservation and restoration of these trails (and anything culturally or environmentally valuable associated with them). Despite this, rapacious landowners have habitually used their power to illegally block cañadas or absorb them into their own landholdings. Hence some routes exist only on paper, many are illegally blocked at some point and others have degenerated into narrow little used paths but many remain as gravel tracks with generous borders. Cañadas (in the north called carrerada or valgada) fall into three main categories: Cañada Reales: tracks up to 75m wide. Cordel: tracks not above 37.50m wide (literally a 'string') Vereda: tracks not above 20m wide (a 'sidewalk') For the most part they seem to be named for the places they link but they are also named after topographical features or the trades using them. Not surprisingly, today they more used by walkers and cyclists than herders. Happily for naturalists those broad untamed margins are a perfect reservoir for wildlife. They can also act as unexpected sources of cultural, social and historical information as I discovered when researching the Cañada de Marchantes (Merchant's Droveway) as noted in my previous post.

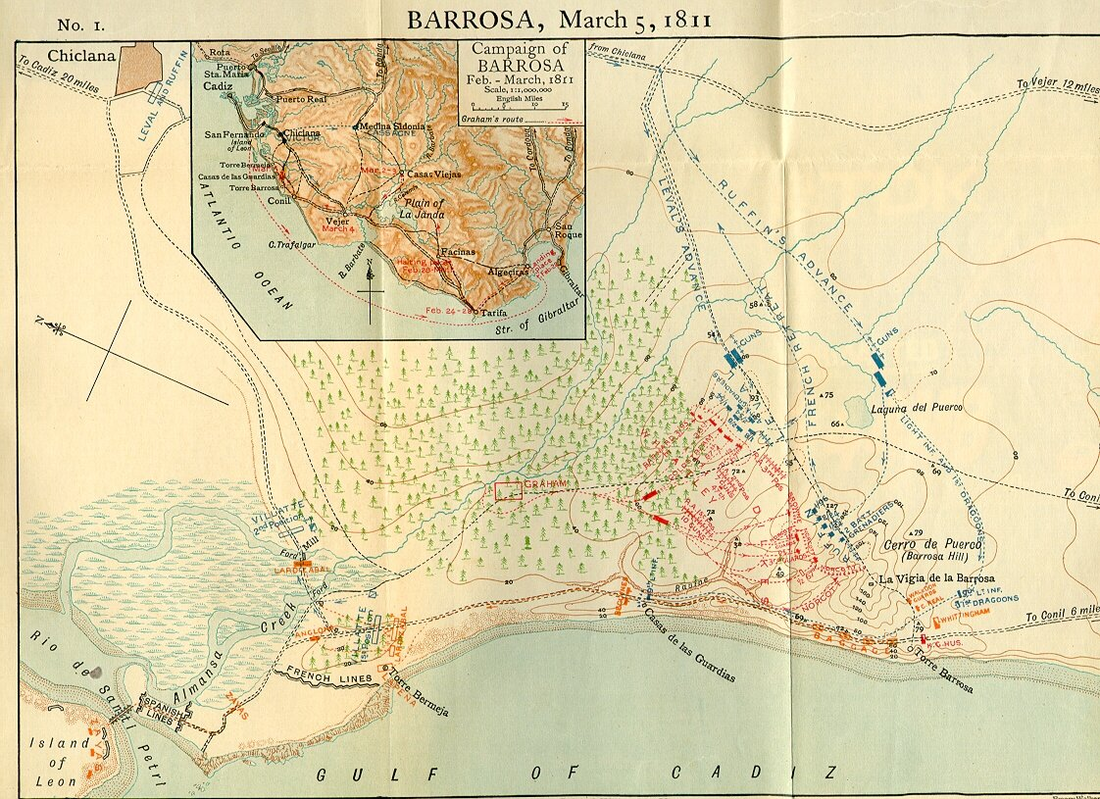

With the help of "Google Translate" I managed to resolve all but one of my questions. The word that remained, "Paquiro", was obstinately obscure no matter how many dictionaries, online and otyerwise, I consulted. However, this too was explained when my good friend Luis-Mi Garrido Padillo explained that it was a name. So thanks to Google, Luis-Mi and with a little editing by myself this, I discovered, was what was written: Magic Point - Miralamar. Our Romantics and seafarer forebears rightly called this place Miralamar (Sea View). The sea, the bay (of Cadiz), Chiclana and its countryside, a whole wide horizon is viewed from this hill where Paquiro had his vineyards and the drovers' road takes us to the lagoons of Jeli and Montellano and 'Cortijo del Ingles'. Chiclana de la Frontera VII centenary 1303 - 2003"  Paquiro - Francisco Montes Reina Paquiro - Francisco Montes Reina "Paquiro" was the nickname of Francisco Montes Reina who was born in Chiclana in 1804. Abandoning his ambition to become a surgeon due to his father's financial problems, he turned instead to bullfighting. Reina remains one of the most famous names in bullfighting history, having codified rules for the corrida and introduced the matador's now traditional "Traje de Luz" (Suit of Light) and hat, the Montera. Indeed, the toreador's headgear is named after him (from his family name Montes). Whatever your personal views about bullfighting, it's clear that Paquiro was a considerable local celebrity whose memory was so important to the town that almost 200 years after his birth (and over 150 years since his death) it was felt it important to name him on this monument. That he is still revered by many in his hometown, a traditional area of support for bullfighting, is also reflected by the fact that there's a museum dedicated to him and bullfighting in Chiclana. The view from Punto Magico is indeed extraordinarily spectacular encompassing, as the inscription tells us, a wide panorama across the sea and the hinterland of Chiclana. Yet so wide and open is the view that it's difficult to do justice to it in a photograph (particularly one of mine). Today it seems a somewhat out of the way place to commemorate Chiclana's septcentenary but I would imagine that it was chosen as from this point all the factors that shaped the town's history are visible from here. The sea that provided both sustenance and, until the coming of the railways, the best means of transport (although it wasn't until 2009 that a tramway linked Chiclana to the 19th century line to Cadiz). The 'Cortijo Ingles' mentioned on the inscription may seem surprising given that this view looks out towards Cadiz the scene of Drake's (in)famous 'singeing of the King of Spain's beard' when, in spring 1587, the English privateer sacked the place (and in the process gave the English a taste for 'sack'). However, it was also near here that the British tried to break the Napoleonic siege of Cadiz at the Battle of Barrosa (Chiclana, 5th March 1811). Despite a single British division defeating two French divisions and captured a French regimental eagle, the British were unable to break the siege and the French continued the siege and held Chiclana until August the following year. Subsequently, British investors became heavily involved in the sherry trade and it is probably then that the farmhouse was given its name (one of several farms in the province so named). All of this, of course, will be lost on determined monomanic birders who will have eyes only for the avian delights of the area which, with luck, can include the declining and much sought after Rufous Bushchat!

|

About me ...Hi I'm John Cantelo. I've been birding seriously since the 1960s when I met up with some like minded folks (all of us are still birding!) at Taunton's School in Southampton. I have lived in Kent , where I taught History and Sociology, since the late 1970s. In that time I've served on the committees of both my local RSPB group and the county ornithological society (KOS). I have also worked as a part-time field teacher for the RSPB at Dungeness. Having retired I now spend as much time as possible in Alcala de los Gazules in SW Spain. When I'm not birding I edit books for the Crossbill Guides series. CategoriesArchives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed