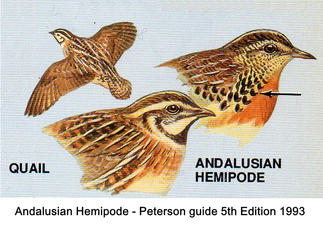

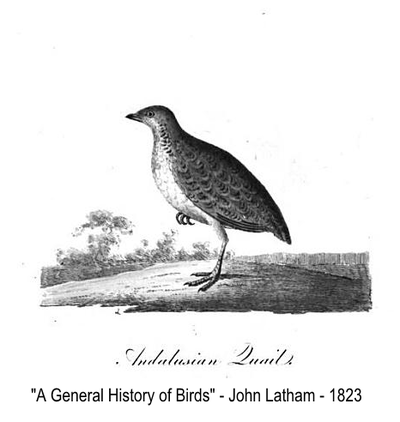

Note that the eye is incorrectly shown as darker than a Quail's

Note that the eye is incorrectly shown as darker than a Quail's  La Caille de Bois' from Desfontaines 1787 book

La Caille de Bois' from Desfontaines 1787 book

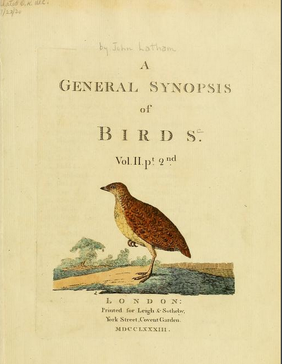

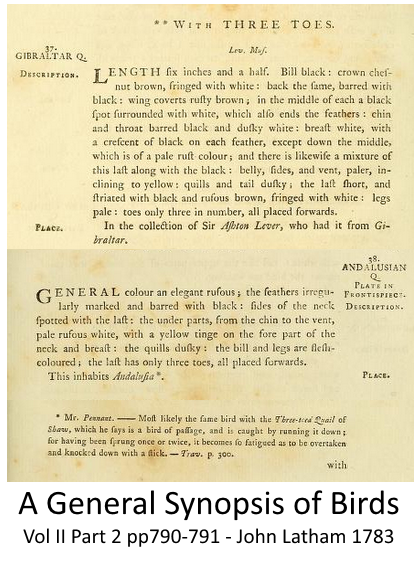

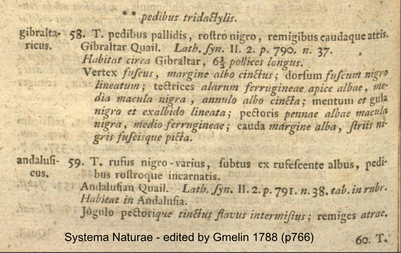

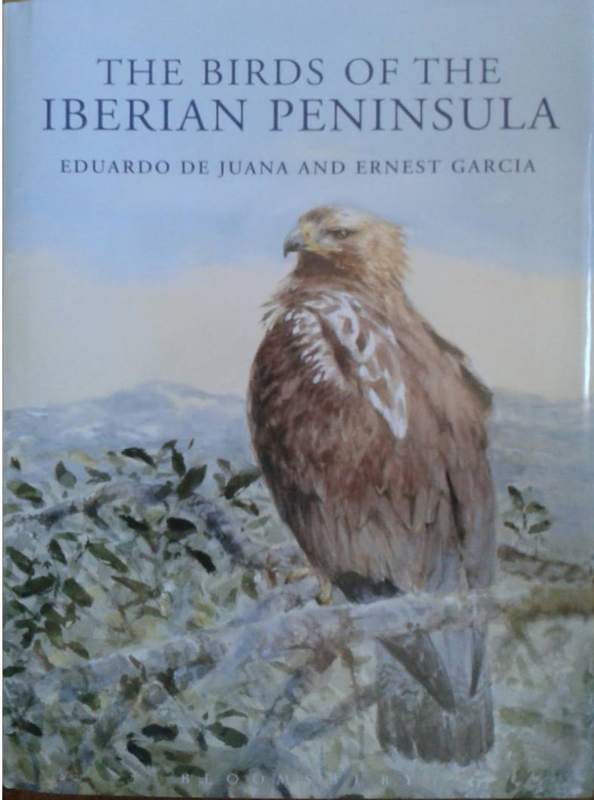

Frontispiece of 'A General Synopsis of Birds Vol II - 1783

Frontispiece of 'A General Synopsis of Birds Vol II - 1783

'European Bush Quail' from Irby's book

'European Bush Quail' from Irby's book

- Before starting your search offer up prayers to whatever deity you prefer (if any) and, if successful, quickly buy a lottery ticket.

- Respect the species' critical conservation status and the sensitivities of landowners by gaining permission to search fields. Some accounts of those who've visited the site seem to me to have broken or at least 'bent' the cardinal rule that the 'bird comes first'.

- Look for their tracks (three toes symmetrically spread like an arrow) and distinctive droppings (small cylindrical and pale greenish) rather than scanning the habitat (chances of seeing them without finding other evidence of their presence is extremely low).

- Listen for the distinctive call – note that the use of 'playback' is probably illegal without proper permissions and ineffective since female do not seem to respond.

- notify the relevant authorities asap (contacting Carlos Gutiérrez would be a good start - [email protected]), but be circumspect about who else you tell as failure to observe point 1 could have catastrophic consequences.

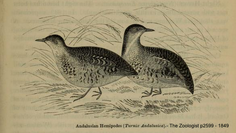

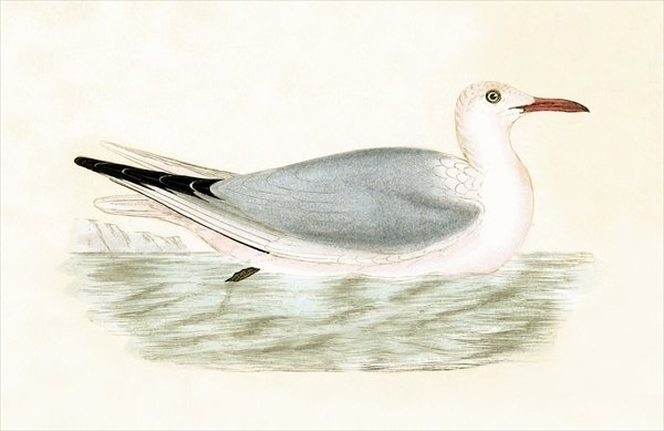

Engraving from 'The Zoologist' (1849)

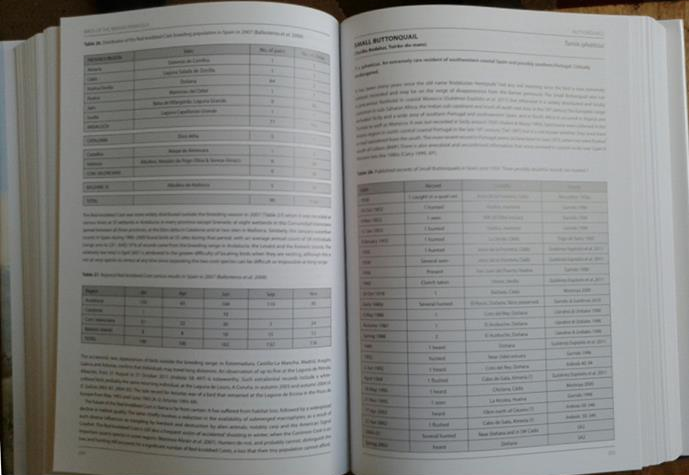

Engraving from 'The Zoologist' (1849) Mention of the claimed British record is just too tempting to be neglected! The improbability of vagrancy seems obvious today, but in the early days of ornithology the background knowledge we so easily take for granted was entirely absent. Even so it is somewhat startling to discover that Andalusian Hemipode briefly had a place on the British List! Although not directly relevant, I can't resist retelling the story. In 1845 “The Zoologist” published a letter from a Mr Thomas Goatley which reported that on 29th October 1844 an Andalusian Hemipode was shot by a Mr R Webb gamekeeper to Miss Pennyston of Cornwell near Chipping Norton and followed by another a few days later. Mr. Edward Newman, to whom Mr. Goatley sent the bird, accompanied by a photograph, later, composed a fuller account, complete with an engraving, for 'The Zoologist' (1849 see - (http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/123055#page/303/mode/1up). It's hard not to speculate which of those persons mentioned had a relative or friend stationed in Gibraltar! Whilst the record must be spurious, it is surely one of the first rarity claims to be supported by a photograph! Newman wrote that more reports would be bound to follow and, sure enough, another was claimed for Yorkshire in 1865.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed