|

Many thanks to Stewart Hingston for sending me photos of the new access road for Cazalla. He also tells me that it appears that work is in hand to renovate and do up the buildings there which were originally intended to house a small exhibition and possibly a modest venta. Sounds good to me although I suspect it'll mean you'll have to get there early on good days to secure a parking space!

0 Comments

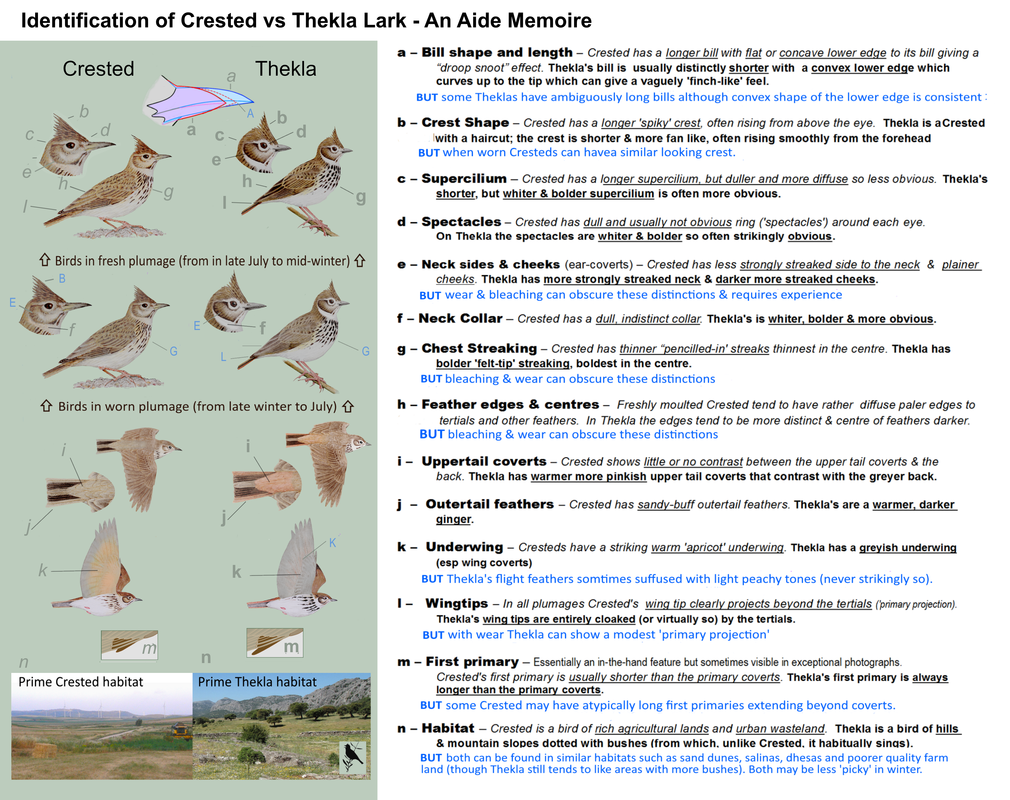

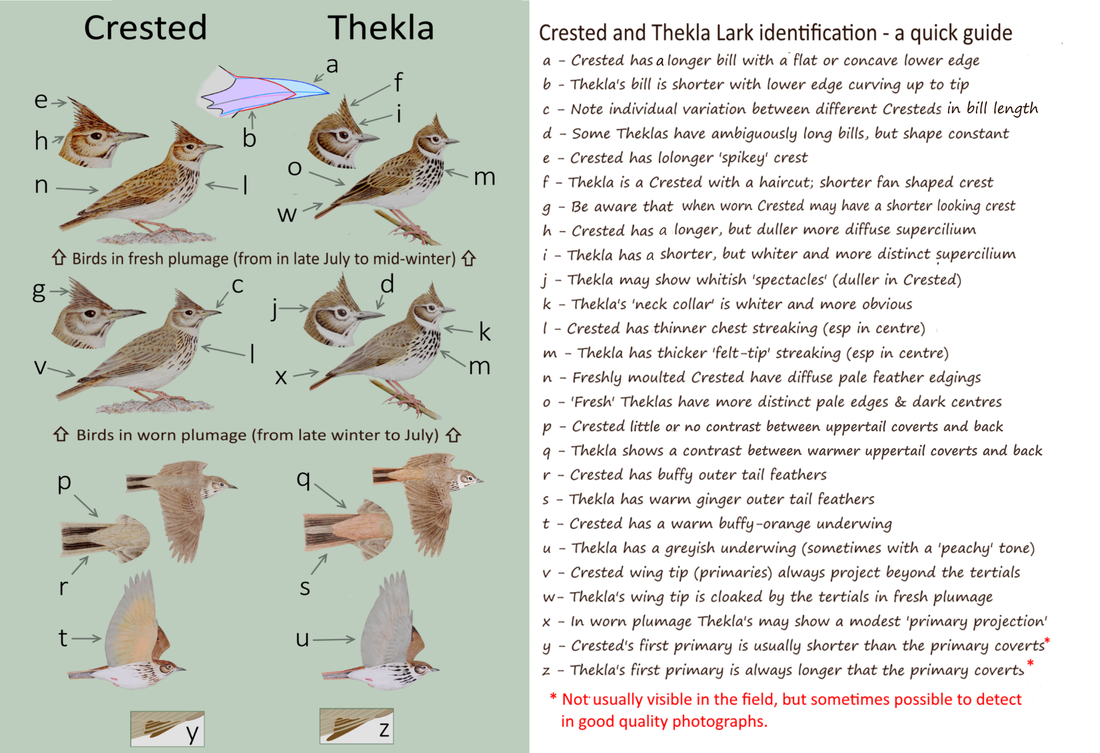

Following some very helpful and constructive comments on 'Bird Forum' I've completely revised and redrafted my comments. Hopefully they're now easier to digest and in a final form. I've experimented with colour coding the notes with caveats highlighted in blue. I hope this helps. Any constructive comments very welcome.

Since originally posting a note on the identification of Thekla and Crested Lark ID a week or so ago, I've redrafted the drawings several times. Disembodied tails and wings have grown bodies. A magnified bill has materialised. The text has been revised and reordered. So many changes indeed that I've deleted the first draft. Apologies to those who were kind enough to make comments.

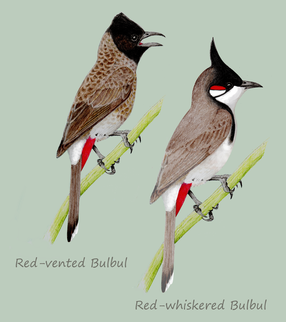

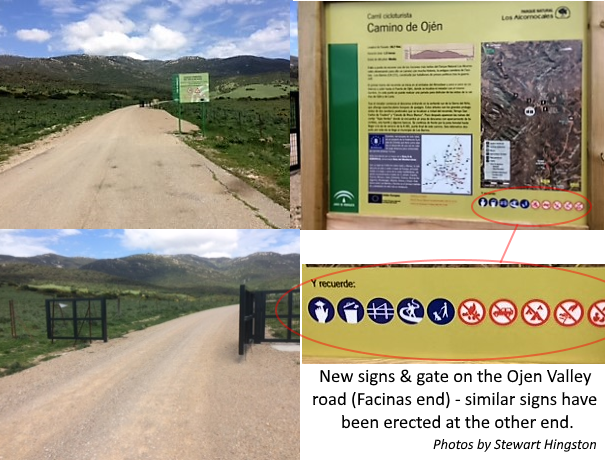

Ojen Valley Ojen Valley Birders have been using the Ojen Valley road (SW.14 in my site guide) for decades, probably a generation or more. It's featured in birding site guides since the early 1990s at least. However, I'm informed that, for reasons best known to themselves, the authorities have instructed the Guardia Civil to stop 'unauthorised' vehicles using the route and to prosecute offenders. At a time when the province is initiating policy to encourage birding tourism this seems a retrograde step. It's bizarre how they don't seem to have the resources to stop the blantant disregard for regulations by kite surfing at Playa de los Lances, but can faff around stopping birders using this route. I'm still making enquiries about this retrograde measure .....  Torre Guadalmesi Torre Guadalmesi Rather less surprisingly, the military authorities now seem to be cracking down on people driving through the mothballed military camp ("Cascabel") and down to the Torre Guadalmesi (site SW 10.3). Offenders have been escorted back to the main road and sent on their way. My understanding is that you can still park at the top of this road, walk down towards the camp diverting round it to your left, then rejoin the track beyond the camps and continue to the coast There really are aliens amongst us. They may not be of the bug-eyed monster variety, but they're certainly 'aliens' in the wider sense of the word. Like so many ex-pats they've found themselves in Spain for a variety of reasons, but they've liked what they saw and decided to settle down. The aliens I have in mind are those exotic birds that have made their home in Spain and, particularly, in Andalucia. In this, the second of my posts on such birds (the first being on parrots), I'm going to look at a couple of species that haven't 'made it' (yet!) and one that seems well on its way to spreading widely in Spain. Once again the excellent blog spot http://grupodeavesexoticas.blogspot.co.uk/ , which lists some 120 species of exotic birds that have been recorded in the wild in Spain, has been a useful source of information. I recommend people report all sightings (with details) to this worthwhile site. Although there's an element of observer bias involved (some widespread birds are badly under recorded), this site does give us a fair reference point from which to start. Of all of these birds about 100 have been reported under ten times (and usually as singletons) so most can be dismissed as serious contenders as colonists. Of the remaining twenty odd species only about half have established a robust foothold in Spain, but what makes one species a success and another a failure? I have no ready answers to this conundrum, but I do have a few ideas .... Firstly successful colonists tend to be birds with a large, rather than restricted, range which in itself indicates another likely factor, a high degree adaptability and a lack of fussiness about what they eat. Secondly they're don't tend to be long distance migrants. Some wildfowl, which do migrate long distances in winter, seem to break this rule, but this ignores that many populations are of wildfowl are sedentary. Thirdly successful immigrants tend to thrive in a similar climate and environment as the one that they occupy naturally. Finally, there should be a vacant niche for them in their new home. -  So why is it that some species that appear to fit these criteria seem unable to expand their range in Spain? Red-vented Bulbul has a large range across across the Indian subcontinent where it's found in hot dry scrub, forest edges, cultivated lands and, crucially, in urban areas. This range encompasses hot tropical areas, Himalayan foothills and areas with a broadly Mediterranean climate. It even has a notorious reptuation as an invasive species being listed as one of the worst and most damaging hundred invasive species. It's established itself in the wild on Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Hawaii and other Pacific islands, in Dubai, Bahrain, USA, New Zealand, Argentina, South Africa, Argentina and elsewhere. So you'd imagine that it was well set to conquer Iberia by storm. Yet although it has been breeding Torremolinos since at least 2000, it still seems to have only a tenuous foothold there and there are no signs of the expected expansion. The same appears true of Red-whiskered Bulbul which has maintained a small populaton in Valencia for a similar length of time.  The two bulbuls lack of success is in distinct contrast to that of Black-headed Weaver. This widespread African species first found a home in Iberia in the 1990s when they were found in Portugal where they have built up a large population. It's an open question whether the growing Spanish population stems from this sources or independent introductions. The latter seems perhaps more likely, but there's no clear cut evidence either way. In both countries they are closely associated with rice fields. Confusingly, early reports of weavers from Portugal refer to the very similar Village Weaver (Ploceus cucullatus) which, to add another layer of confusion, is sometimes also called Black-headed Weaver! However, the bird involved is the 'other' Black-headed Weaver (Ploceus melanocephalus). It's also worth noting that in the Iberian population many males (like all females) have pale irises which contradicts most field guide illustrations of this species which show them as being dark. I've always thought that pale eyes may hint at a mixed genetic heritage (not unusual in cagebirds), but I've also been told that the guides are wrong and that in some wild populations of the species male melanocephalus in Africa do show pale eyes. Rather surprisingly neither the two Spanish atlases (breeding & winter) nor do de Juana and Garcia mention the species as occurring in Spain (although its presence in Portugal is noted). Yet they were present and breeding at Brazo de Este in 2006 when it was said they had been present for “several years” and their presence ascribed to escapees from the cagebird trade. However, the population must then have been fairly small and discrete as several expert visitors to the area at that time (and before) fail to mention them in trip reports (although waxbills and bishops were noted). In 2011 local expert Paco Chiclana reported them to be expanding and occupying more habitat at Brazo del Este and nearby wetlands. By 2015 the same author described them as 'numerous' at the same site and noted that they were establishing themselves in similar habitat near Utrera and Las Cabeszas de San Juan. In the same year a lone bird was found at Guadalhorce (Malaga). It seems likely that more areas will be colonised and this attractive bird will follow its African and Asian neighbours to become a permanent fixture in Spain. Why the difference? In truth I don't think anyone knows for certain. The climate in Spain is reasonably similar to areas that bulbuls have successfully colonised so this alone wouldn't seem to be a barrier. It may be that the habitats which the bulbuls find themselves in is too isolated or subtly 'wrong' for the species (although, once again, they seem to have managed elsewhere). In the case of the weavers it seems that they've found, in large rice paddies and surrounding ditches, not only an ideal subsitute habitat, but also a vacant niche. It may also be that the bulbuls suffer from an exceptionally high level of predation from threats like feral cats. However, my favourite theory is that the success or failure of colonists depends on the size of the 'founding population'. I doubt that many entirely successful colonisations have resulted from birds escaping in dribs and drabs and meeting up in the wild through lucky happenstances. It's far more likely that they are the result of mass escapes (or releases) from breeders or importers. Unfortunately the precise moment of release is rarely documented although in rare cases the apperance of feral birds has been traced to a single mass release by the cagebird trade of 'uneconomic' stock. A very small founding population may also compromise the colonist's gene pool making them vulnerable to disease. It is this, it is ususpected, that has caused the sudden and dramatic decline in some would be colonists that had previously been doing well.

|

About me ...Hi I'm John Cantelo. I've been birding seriously since the 1960s when I met up with some like minded folks (all of us are still birding!) at Taunton's School in Southampton. I have lived in Kent , where I taught History and Sociology, since the late 1970s. In that time I've served on the committees of both my local RSPB group and the county ornithological society (KOS). I have also worked as a part-time field teacher for the RSPB at Dungeness. Having retired I now spend as much time as possible in Alcala de los Gazules in SW Spain. When I'm not birding I edit books for the Crossbill Guides series. CategoriesArchives

May 2023

|

| Birding Cadiz Province |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed