|

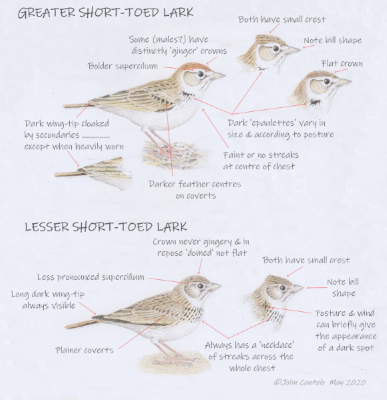

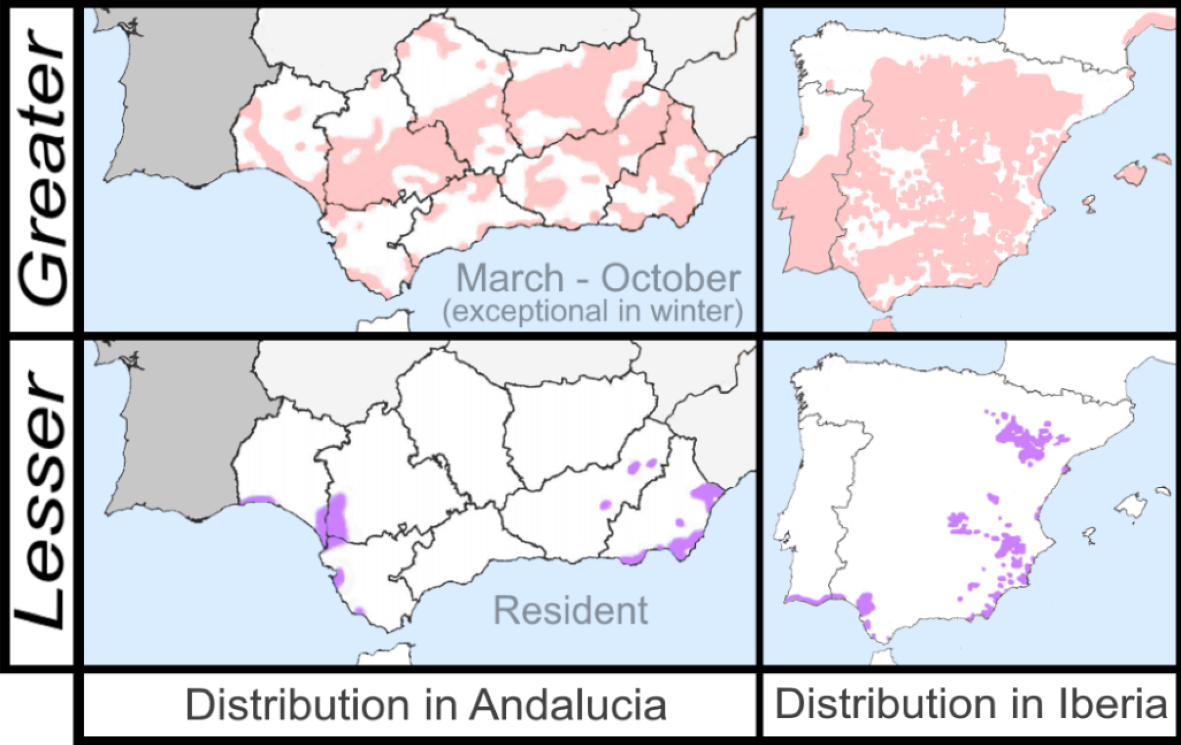

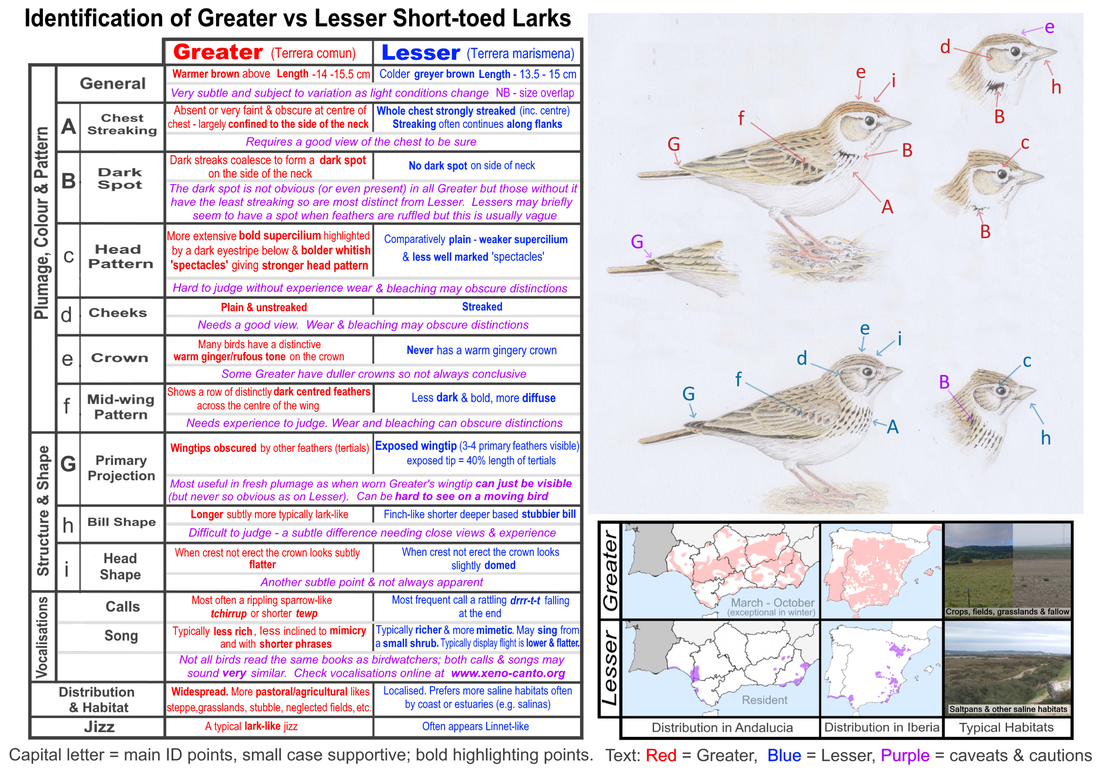

To the untutored eye all larks look quite alike sharing a broadly similar structure, gait, tweedy plumage pattern and, more often than not, a crest of some sort. Skylark, Crested and Thekla’s Lark are generally noticeably larger (in length and in bulk) than ‘short-toed’ larks (although a small Thekla’s can overlap in length) and the latter two at least have a more obvious crest. Woodlark is a similar length but generally heavier and has distinctive plumage markings. So even with a modest amount of experience it should be possible to recognise that the bird in question is one of the ‘short-toed’ variety. As so often in these matters when a bird is seen can provide a useful clue (although caution is needed as this can sometimes be a ‘false friend’). Greater are a summer migrant to Iberia which appears from mid-March onwards but only starts to arrive in force in April. Autumn passage starts by mid-August with most leaving in September (although a few linger into October). Lesser are residents so any small lark observed between mid-October and early March should be that species. Should be, but not necessarily will be since wintering Greater have recently been seen in consecutive years in the Osuna area (Seville) and there is, of course, a possibility that global warming will make such instances more frequent. That said, in practical terms the exceedingly rare records of wintering Greater can be safely ignored. Similarly, habitat and range can help too. Birds found in agricultural areas with a little scrub, on ploughed fields, fallow, set aside, grassy areas, vineyards or even orchards will, in almost all instances, be a Greater. Lesser is predominantly an habitué of natural vegetation that’s dominated by low salt-resistant scrub with little grass on poor soils and, particularly in the west, has a preference for salt marsh. This is reflected in the Spanish name for Lessers, Terrera Marismeňa (similarly helpful is the name for Greater are Terrera comun which reflects its relatively widespread status). Accordingly, a good rule of thumb in Andalucia is that any small lark found beyond c25 km from the coast or away from estuarine saltmarsh will be a Greater. An exception must be made, however, for the Hoya de Guadix and Hoya de Baza (Granada) which are both shallow basins where saline conditions dominate providing good habitat for Lessers. (The applies to similar habitat in central and eastern Spain, the Ebro valley and across the species’ range in Asia). Just to confuse matters in winter Lesser sometimes appear in the ‘wrong’ habitat such as ploughed fields (fortunately when Greater should be absent). Greater also do their bit to confuse by inhabiting dune systems near salt marshes and along grassy embankments that intrude into “typical” Lesser habitat. For example, the first Lessers I ever saw were in a grassy dune slack on the Ebro delta where there were also Greaters. Conversely, a Greater I saw on the Barbate estuary one recent spring flew from its typical grassy habitat to feed in the sort of saltmarsh habitat that Lessers generally prefer. However, even when all these caveats are considered, habitat preference remains a useful clue. These habitat preferences are clearly evident in the two species distribution in Andalucia. So once you’ve found a “short-toed” lark, setting aside consideration of the season and habitat, how can you go about confirming its identity? There are three main factors that should help you resolve identification; the presence or absence of streaking across the chest, the presence of a dark spot on the neck and the structure of the birds’ wings. There are other helpful pointers concerning plumage and structure plus variations in voice and sometimes behaviour (but these are secondary to the three are clinching points noted above). However, although these differences may be small small and sometimes confusing in themselves, collectively tend to give the two species a different ‘feel’ or ‘jizz’. Taking plumage first the key plumage distinction to look for is the pattern of streaking (or its absence) on the chest and the side of the neck. Greater tends to have streaks restricted to the side of the neck or, when present, only very faint, thin streaks running towards (rarely across) the centre of the chest. On the side of the Greater’s neck the streaking usually coalesces to form a dark ‘spot’ and, although posture can make this more or less obvious, most birds show this feature. Those Greaters that don’t have a dark spot have such indistinct and sparse streaking that this alone rules out Lesser. In contrast, Lesser lacks the dark spot (although occasionally might briefly seem to have one when the breeze exposes its darker underlying downy feathering) but always has strong streaking across the entire chest (including the centre) forming a distinct ‘gorget’ contributing to its resemblence to a female/juvenile Linnet) and such streaking often extends along the flanks. The Greater’s head pattern is usually subtly stronger with a bolder, more extensive buff-white supercilium highlighted by a darker eyestripe below plus more striking whitish ‘spectacles’. An exception are the ear-coverts (= cheeks) which are rather plain on Greater but more distinctly streaked on Lesser. Greater also often (but not always!) has a warmer or even distinctly ‘ginger’ crown which Lesser never shows. This is mirrored in the general tone of the two species’ upperparts (in Iberia) as Lesser tends to be a greyer, less warm brown than Greater (but without direct comparison and with varying light conditions this can be very hard to judge). Although wear and bleaching can reduce the distinctions, the general impression is that Greater‘s head appears more lark-like whilst Lesser‘s more resembles a Linnet. Another subtle clue in a bird’s plumage that can be looked for is the pattern of the “median coverts” (roughly the feathers that run across the centre of the closed wing). In both species these show dark centres but in Lesser this is often confined to the shaft streak or rather diffuse whilst in Greater it’s bolder, darker and so more obvious. This may seem to be obscure but in the right conditions on some distant birds it can be the first clue you notice. The presence or absence of a distinct ‘primary projection’ is the third critical feature to look for. The term primary projection may seem technical but in simple terms it means whether and how far the primary feathers (colloquially the ‘wing tip’) extend beyond the cloaking feathers of the inner wing (‘tertials’) when the bird is at rest. On Lesser 3 or 4 primary feathers extend well beyond the tertials and are c40% as long as them. On Greater the wing tips are entirely (or almost so) concealed by the tertials with at best only a small nub visible beyond them. Even on heavily worn birds only one or two wing tip feathers are normally visible. This means that the Lesser’s wing tip is plainly visible on a resting bird but has to be carefully looked for on Greater (although it must be admitted that on both it’s easier seen in photographs as not every lark is so co-operative to pause for a while). There are a further two minor and admittedly very subtle clues to be noted when looking at the structural differences between the two, head and bill shape. The small crests of both species are only visible when erected and pretty much identical but in repose the crown of Greater tends to be marginally flatter than that Lesser which can look slightly more rounded. The bill of Greater tends to be longer (and averages paler) than Lesser’s slightly stubbier bill. The harder one looks for these distinctions then the less obvious they often seem to be but both may subtly contribute to the Greater’s more lark-like feel and the Lesser’s resemblance to a small finch. Voice can provide another clue for those sufficiently experienced to be well attuned to vocalisations. Both the calls and songs have a generic ‘lark-y’ feel to them but are so similar that accurately conveying these distinctions in written form is highly problematic. In very broad terms Lesser’s most frequent call is a dry, rattling (or purring) ‘drrrr-t-t’ which usually slows or falls at the end whereas Greater has a shorter ‘tewp’ and a rippling ‘tchirrup’ (sometimes recalling a sparrow). However, there’s a good deal of variation and both species can sound very alike. The song is similarly difficult to define and describe. Lesser tends to have a rich, rather varied and faster song which is more likely to include mimicry of other species (including Greater and other larks!) although inclusion of its rattling call can help. Confusingly Greater appears to have two song types; one using short phrases (1-3 secs) given at low level (?) and another with longer phrases given at greater heights. Another clue is that Lessers typical circling song-flight is lower without distinct undulations often accompanied by slower, higher wingbeats (reminiscent, perhaps, of Greenfich display) but they can also fly higher when, just to confuse matters, they can sound more like a Greater! Both species also sing from the ground but Lesser (apparently unlike Greater) will also sing from a small bush or shrub. However, individual variation, changing conditions mean these subtle distinctions can mean little in the field unless you’re highly experienced with both species. Accordingly, I advise those with good hearing and a good aural memory to listen to multiple recordings of calls and song on xeno-canto (Greater - https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Calandrella-brachydactyla; Lesser - https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Alaudala-rufescens) but make sure those you listen to come from western Europe as there is some variation between different subspecies. I've put all of these points in tabular form on a pdf (see below) which is available on request.

0 Comments

|

About me ...Hi I'm John Cantelo. I've been birding seriously since the 1960s when I met up with some like minded folks (all of us are still birding!) at Taunton's School in Southampton. I have lived in Kent , where I taught History and Sociology, since the late 1970s. In that time I've served on the committees of both my local RSPB group and the county ornithological society (KOS). I have also worked as a part-time field teacher for the RSPB at Dungeness. Having retired I now spend as much time as possible in Alcala de los Gazules in SW Spain. When I'm not birding I edit books for the Crossbill Guides series. CategoriesArchives

May 2023

|

| Birding Cadiz Province |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed