Gibraltar in 1782

Gibraltar in 1782

Lord Lilford

Lord Lilford  'Observer's Book of Birds'

'Observer's Book of Birds'  Howard Saunders

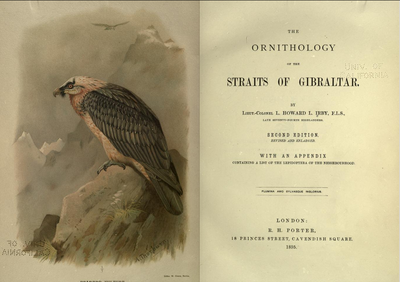

Howard Saunders  Lt-Col Howard Irby

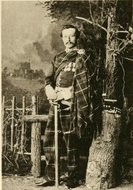

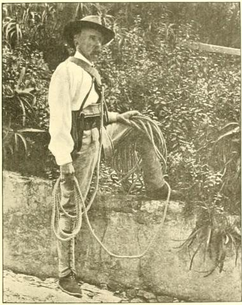

Lt-Col Howard Irby  Willoughby Verner - an expert climber

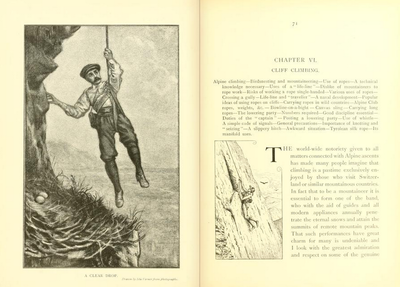

Willoughby Verner - an expert climber Although Verner was posted to Gibraltar in 1874, he and Irby first met on Tiree, in 1877; it was the start of a long friendship and fruitful collaboration. Although a man of many talents, being a soldier, military historian, artist, inventor, climber, speleologist and antiquarian, Verner’s overriding passion was natural history. As noted above he contributed many notes to the second edition of Irby’s work having retired to Algeciras at the end of his military career. Today his “My Life among the Wild Birds in Spain” (Pub. 1909 - see https://archive.org/details/mylifeamongwildb00vern) makes somewhat uncomfortable reading given his evident glee in birds nesting (as he euphemistically called it). Yet there’s no disguising that he was a superlative observer with a deep knowledge of the area and its birdlife. His book contains chapters on the larger and most charismatic birds of the area (particularly raptors and how to reach their nests). There's relatively little on what he somewhat disparagingly refers to as 'lesser birds'. He also pioneered the use of small hand held cameras at a time when their use was disparaged. As a keen antiquarian and expert climber, Verner was also one of the first people to explore Cueva de la Pileta in Benaoján which he helped bring to public notice.

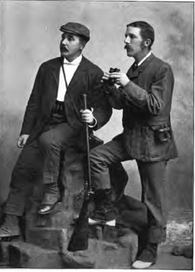

Walter J Buck (left) and Abel Chapman

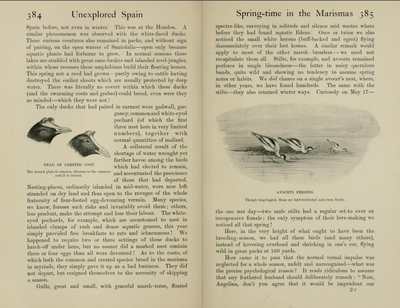

Walter J Buck (left) and Abel Chapman Both books contain much information about the Coto Doňana and, although the main focus is on the larger mammals and gamebirds, they also dealt with the smaller birds, reptiles, insects and plants of the area. It was Chapman who first reported that Flamingo bred there and drew attention to the area’s importance as a migratory route.

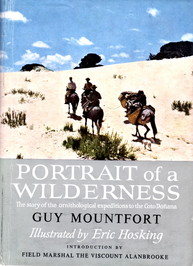

Written in a fluent and interesting style, their books inspired generations of British naturalists; it was ”Wild Spain” that fired Guy Mountfort’s interest and was hence indirectly responsible for his equally inspirational book, “Portrait of a Wilderness” (1958).

John H Stenhouse

John H Stenhouse  F C R Jourdain (left) and H F Witherby

F C R Jourdain (left) and H F Witherby Other ornithological notables such as W M Congreve (1883 - 1967), Collingwood Ingram (1810-1981) and G K Yeates (1910-1995) followed. The latter’s “Bird Life in Two Deltas” (1946) was largely based on visits to the Camargue and Coto Doňana in the 1930s; a copy found neglected in a school library, along with Mountfort’s book (see below), inspired the writer of this note to visit both in the early 1970s. Published in 1938, Robert Atkinson’s ‘Quest for the Griffon’ is the entertaining tale of three, rather naive, undergraduates who drove down to Tarifa just before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. They succeeded in their objective to get close-up photographs of nesting Griffon Vultures, but what would today’s digi-photographers make of the French customs, through which they passed, whose regulations stated that only “two photographic machines and twelve plates” could be imported? Happily the rules were sagely ignored by Atkinson and his friends! Collingwood Ingram, the last of the great “shooting birdwatchers”, visited the area in the 1920s mainly to hunt, but regularly returned in the 1950s and 1960s to watch birds. Wisely, in his later works he omitted his tales of shooting Great Bustards and thrushes! By the early 1950s he was regarded as the British authority on Iberian birds. He too had an interest in the sherry trade.

| This brief account takes us up to the publication of the first European field guide in 1954 so does not include the fifth inspirational book on the wildlife of Spain - “Portrait of a Wilderness” (1958) which describes three expeditions to the Coto Doňana. This is rather apt since all three authors of that guide, Roger Tory Peterson, P A D Hollom and Guy Mounfort, all took part in the first expedition in 1952 when the proofs of their book were given a final check. The story of the three expeditions and their influence is worth an entire article of its own …… |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed