The Helm Guide to Bird Identification

Vinicombe, Harris & Tucker ISBN: 978-1-4081-3035-3

Pub: Christopher Helm RRP: £25.00

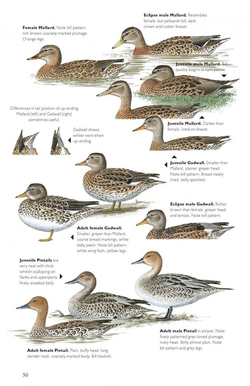

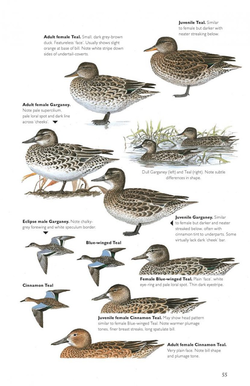

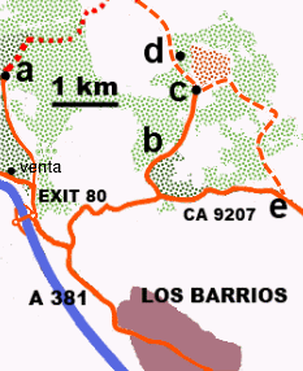

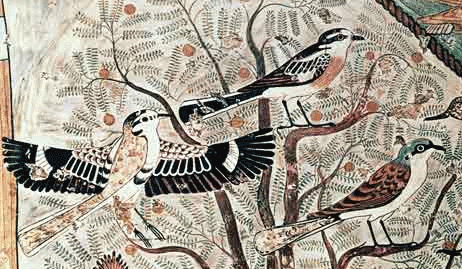

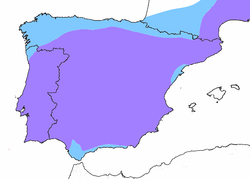

Given the age profile of most birders, many of the more experienced will be aware of the excellent ”Macmillan Field Guide to Bird Identification” (1989) and, I suspect, most will have a copy on their bookshelves. Appearing ten years before the all-conquering ‘Collins Guide’ this and its companion guide (”The Macmillan Birders’ Guide to European and Middle Eastern Birds” – 1996), were the ‘go to’ books for resolving tricky identification problems. This new guide from Helm is an extensive and detailed reworking of this highly regarded original volume incorporating some illustrations from the later volume and adding many more species. The three questions that I have tried to address here are - Do you need this book (especially if you have the original)? Has the ‘Collins Guide’ made it superfluous? How useful is it to Spanish based birders?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed