* Actually that may not be too far from the truth as some scientists believe that Lesser Kestrel, which isn't as close a relation of Common Kestrel as its appearance suggests, has evolved to mimic Common Kestrel and even more so Rock Kestrel, an African species found where Lessers winter, which are both larger and more aggressive thus affording the smaller species' some measure of protection!

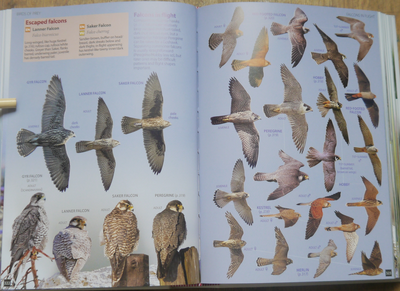

Illustration 1 : 1st summer, note the tail & head pattern, lack of grey wing panel and lack of grey wing panel,

Illustration 1 : 1st summer, note the tail & head pattern, lack of grey wing panel and lack of grey wing panel,  Fig 1: Common Kestrel (left), Lesser kestrel (right)

Fig 1: Common Kestrel (left), Lesser kestrel (right) So how can you tell them apart?

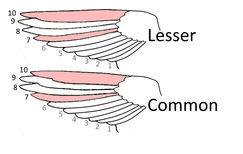

Happily, when perched, first summer has the Lesser's typical dumpier, more round headed shape with wings that approach the tip of the tail (see Fig 1). At times this can look obvious but at other times it's not so easy to detect particularly if you're unfamiliar with the species. Then there's also the distinct wing formulae with Lesser having a far longer outermost primary (P10) although that's best seen in photos of flying birds (see Fig 2)

Fig 2: Note that in Lesser P10 is much longer than P7 whilst in Common they're the same length

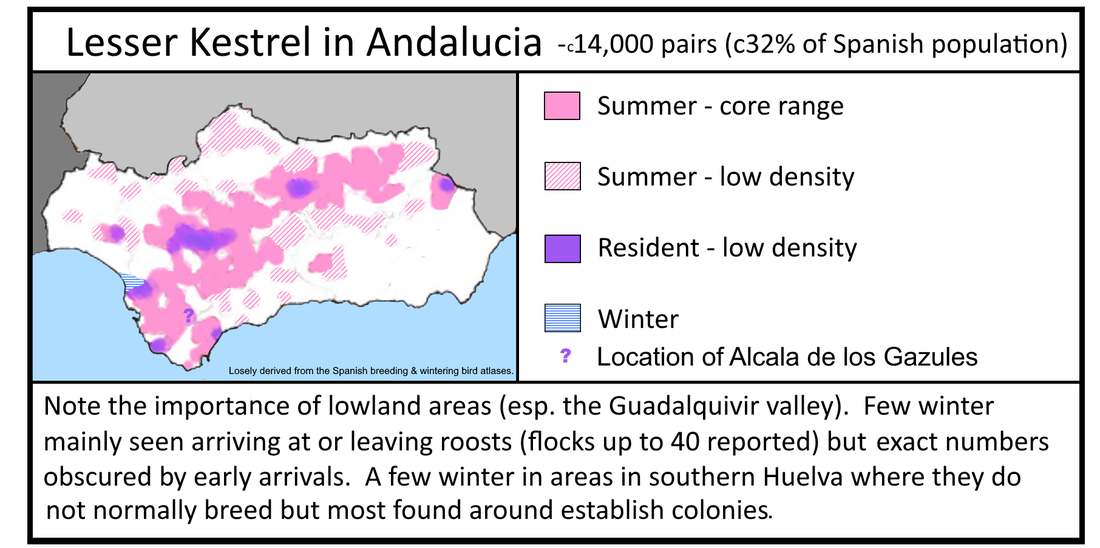

Fig 2: Note that in Lesser P10 is much longer than P7 whilst in Common they're the same length So if you're in Andalucia in winter remember that Lesser Kestrels return earlier than you might think and don't give up on seeing Lesser Kestrel even in mid-winter. So double check those kestrels you see out hunting in November-January and try to visit a lowland village with a thriving summer population just before dusk.

This is a much shortened and amended version of a short article on Lesser Kestrels due to be published in the magazine of the Andalucian Bird Society's quarterly magazine in autumn 2016 (see - www.andaluciabirdsociety.org/)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed