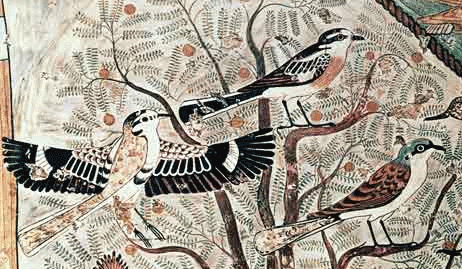

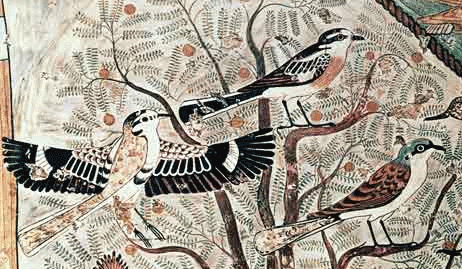

Masked (top) and Red-backed Shrikes from the tomb of Khnumhotep II (c3,800 BP)

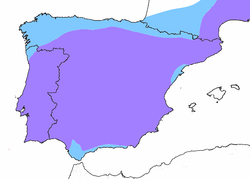

Masked (top) and Red-backed Shrikes from the tomb of Khnumhotep II (c3,800 BP)  Map of Woodchat Shrike distribution

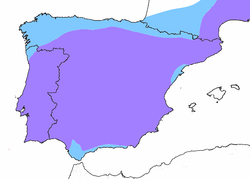

Map of Woodchat Shrike distribution  Map of Iberian Grey Shrike distribution

Map of Iberian Grey Shrike distribution * see my bird guide for more details of these sites

| Birding Cadiz Province |

|

Masked (top) and Red-backed Shrikes from the tomb of Khnumhotep II (c3,800 BP) Masked (top) and Red-backed Shrikes from the tomb of Khnumhotep II (c3,800 BP) There's something about shrikes that gets a birdwatcher's pulse racing. This fascination seems to be a long standing one judging by the care and accuracy with which Masked and Red-backed Shrikes were painted in Egyptian tombs. For starters they're generally rather handsome birds with most sporting dramatic plumage patterns often involving a dark mask and flashes of white on the wings or tail. Even those examples that are less flamboyant, often females or juveniles, may show a pleasingly cryptic plumage with subtle blend of mottling and barring in muted colours. Then there's their bold in-yer-face habit of sitting up on fence posts, roadside wires and bushes surveying their territory. Yet when they want to they can also be frustratingly elusive, hunkering down low in a bush to avoid being seen. They're also somewhat enigmatic; a songbird yet one with a hooked bill and a daunting reputation for ferocity. Smaller shrikes mainly eat insects and small lizards, but the larger Great Grey Shrike (Sp. Alcaudón Real Norte) tends to eat small mammals and birds. They've even been known to take weasels and stoats, albeit young ones, and take on far larger birds such a grouse! Shrikes also have the macabre habit of spiking dead prey items on thorn bushes in a 'larder', something most would find repellent rather than endearing. This is the origin of it's scientific name 'Lanius' (butcher) and the old colloquial name 'butcher bird'. A shrike 'larder' serves several purposes – a store for when prey are elusive, a means to dismember prey and to attract a mate. An elegant, if somewhat mean, experiment demonstrated the latter point when researchers deliberately took items from one larder and added them the a rival bird's store. 'Control' birds (whose larders were untouched) were average at attracting mates, but those with reduced larders did badly whilst those with augmented ones did much better. Most names for shrike, both local and international, reflect the supposedly violent and rapacious nature of the birds. Old English names include wierangle (= destroying angel), throttler, murdering pie and nine killer. The latter name reflects the widespread belief that they have to kill nine times, hence the German name Neuntöter, before their blood lust is satiated. In parts of India they're called khatik which also means 'butcher'. The German name for Great Grey - Raubwürger - means 'plunder strangler' and many other names have a similarly violent connection. An exception is the word 'shrike' which, depending on the authority preferred, comes from either their harsh calls (cf 'shriek') or a misapplication of an old name for Mistle Thrush ('shrite'). The Spanish alcaudón is another exception probably coming from the Arabic al qabṭún meaning 'big head'. Oddly this is also the meaning of 'loggerhead'', a name given to an American species of shrike! Not all ancient lore is so harsh about shrikes. Even the 'neuntöter' slander may stem from a corruption of 'nagel', or nail, rendering its name as a somewhat less bloodthirsty and more accurate one of 'nail killer' (a clear reference to spiking prey on thorns). Most at odds with this violent tradition is another Indian name - gandhari - which was the name of an Indian queen who, in an act of supreme empathy, wore a blindfold (cf the black mask of many shrikes) to better understand her blind husband. For British birders some of the appeal must be the relative rarity of shrikes in the UK. Once fairly common, numbers of Red-backed Shrike (Sp. Alcaudón Dorsirrojo) in the UK dwindled throughout the previous century such that it's been effectively extinct for several decades. Fewer than a couple of hundred now turn up on passage each year whilst about half that number of Great Grey Shrike appear on passage (although as c50 winter they give us more of a chance to spot one). Other shrikes turn up, but all are rare so seeing one in the UK requires a lot of luck or a well used bird news pager! In contrast Spain has three common breeding species of shrike. There were four breeding species, but, unfortunately, Lesser Grey Shrike (Sp. Alcaudón Chico), which always had a limited distribution, is now probably extinct or, at best, only has the weakest of clawholds in Catalonia. Although the three other species have declined in Spain (as they have across Europe), all have populations in excess of 200,000 pairs. As Red-backed Shrike only breeds in northern Spain, here I'll be concentrating on the two that breed in Andalucia.  Map of Woodchat Shrike distribution Map of Woodchat Shrike distribution The striking chestnut crowned piedbald Woodchat Shrike (Sp. Alcaudón Común) is undoubtedly a handsome bird. The females are duller versions of the males, but young are mottled and vermiculated greyish brown. Being so distinctive you'd imagine that the adults present no identification challenge, but diehard enthusiasts might like to try picking out passing birds of the race (badius) found on the Balearics. These lacks the white flash on the wings. It has a rather loud song exhibiting plenty of mimicry (a surprising trait of many shrikes). As its Spanish name suggests, they're the most common and widespread species of shrike in Iberia. They're roughly twice as abundant than Red-backed although estimates of the Woodchat's population vary enormously (500,000 - 800,000 pairs). The two species manage to co-exist over much of the Woodchat's range, but in Spain Red-backed Shrikes are largely found where Woodchats are absent. Given that both species winter in sub-Saharan Africa, you'd think both would be common in Andalucia on migration. Woodchat certainly is, but, counter-intuitively, Red-backed Shrikes are very rare indeed (only three records are listed in the 'Field Guide to the birds of the Straits of Gibraltar'). Despite adding 2,000km to their journey, Spanish Red-backed Shrike don't head south in the autumn, but first fly east before heading through the Balkans, down the Rift valley to southern Africa. This reflects the Red-backed's evolutionary history as a predominantly eastern species. So any claims of Red-backed Shrike in Andalucia, particularly juvenile birds, need to be checked carefully. Woodchat is an essentially Mediterranean breeding species (although they used to breed further north), but they winter in a broad band from Senegal across the Ethiopia. A few Woodchats arrive in March (and some even earlier), but most don't come through until April peaking in the second half of that month. In autumn most leave in August, but a few, usually juveniles, linger as late as October or November. Although small vertebrates are sometimes taken, they mainly feed on beetles and grasshoppers which explains why they head south in the autumn. They're so common in Cadiz province that they should be possible almost anywhere there's suitable habitat (open areas with scattered trees or bushes).  Map of Iberian Grey Shrike distribution Map of Iberian Grey Shrike distribution The second regularly breeding species is the …. well, there's the rub, nobody seems quite sure what to call the medium sized grey shrike found across Spain. Twenty years ago this wasn't a problem, it was the Great Grey Shrike in Spain just as it was across the rest of Europe and beyond. Field guides only illustrated the race (excubitor) which is found across northern and central Europe hardly mentioning that birds in Provence and Iberia (meridonalis) were subtly distinct. It wasn't until the 1990s that they were well illustrated; first in Vol. VII of the 'Birds of the Western Palearctic' (1993) and then in a new edition of 'Collins Pocket Guide' (1995). Spanish birds are darker grey above, have a more distinct white line above the black mask, less white on the 'shoulders' and are pinkish-grey (not white) below. Not a huge difference but easily visible in the field. By the late 1990s these birds, along with others ranging across Africa, Arabia and India, were split as 'Southern Grey Shrike'. However this soon proved to be something of a 'ragbag' of different forms so it's now generally called 'Iberian' Grey Shrike (Sp. Alcaudón Real Meridonal). However, it's still not clear whether birds in north Africa or the Canaries should be lumped as 'Iberian' or 'Southern' Grey Shrike. All these changes reflect the taxonomic revolution caused by the developing science of DNA. Bizarrely, this has shown that Iberian Grey Shrike is more closely related to the American Loggerhead Shrike than Great Greys from northern Europe. About 200,000 meridonalis breed in Iberia with a further 2,000 in Provence making it a near Iberian endemic. One by-product of all this confusion over the birds' name and appearance is that the status of Great Grey Shrike (as it's now recognised) in Spain is quite obscure and nobody seems quite certain just how regularly they might occur. Unlike Woodchat, Iberian Grey Shrikes are residents although in winter birds wander more widely. The map probably overstates their status a little as there are several areas where they seem strangely absent or at best very thinly spread. Like Woodchat they also eat beetles and grasshoppers, but depend far more on larger prey such as small vertebrates (often lizards) plus a few small mammals and the odd bird. Being less dependent on invertebrates explains why this shrike is able to survive winter in Spain. In Cadiz they appear to be pretty much restricted to Grazalema (see *E3.2 Ubrique-Grazalema road & *E4.2 Llanos de Libar) as breeding birds. In Seville province the appear tolerably common breeding bird in the young olive groves and vineyards near Osuna (see *SV 6 – Osuna Farmlands). Happily they're more widespread on during the autumn and winter when I've seen them around Alcala (*SW 1 Embalse del Rio Barbate and *E2.1 Molinos valley) although they're certainly more widespread. * see my bird guide for more details of these sites

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About me ...Hi I'm John Cantelo. I've been birding seriously since the 1960s when I met up with some like minded folks (all of us are still birding!) at Taunton's School in Southampton. I have lived in Kent , where I taught History and Sociology, since the late 1970s. In that time I've served on the committees of both my local RSPB group and the county ornithological society (KOS). I have also worked as a part-time field teacher for the RSPB at Dungeness. Having retired I now spend as much time as possible in Alcala de los Gazules in SW Spain. When I'm not birding I edit books for the Crossbill Guides series. CategoriesArchives

May 2023

|