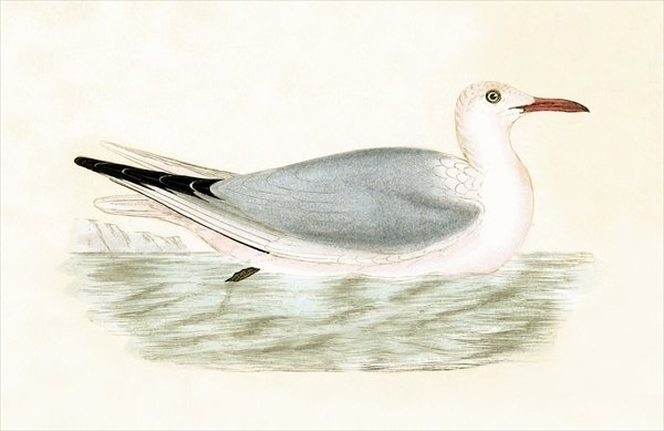

Slender-billed Gull - from 'A History of the Birds of Europe not observed in the British Isles' by Charles Beebe (1867).

Slender-billed Gull - from 'A History of the Birds of Europe not observed in the British Isles' by Charles Beebe (1867).  D I M Wallace's line drawing from his paper showing the distinctive shape of Slender-billed on the water.

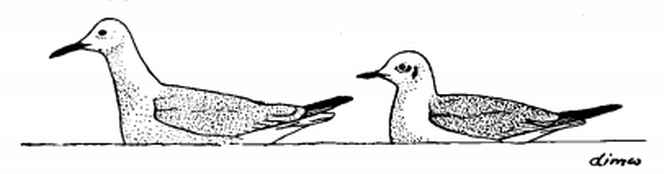

D I M Wallace's line drawing from his paper showing the distinctive shape of Slender-billed on the water.

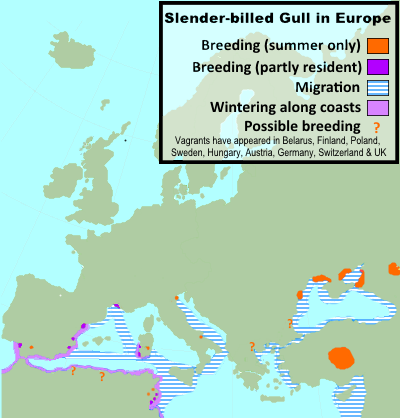

Fortunately I didn't have to wait quite so long for my next sighting since, now divested of a mortgage and responsibility for my children, but, happily, not my wife, I was able to start visiting souther Spain regularly from 2005 onwards. If much had changed in my life then so too had things changed in the fortunes of Slender-billed Gull! Happily following its resurgence there are now three regular colonies in western Andalucia – all three, Marismas del Guadalquivir and Veta la Palma (Seville) and Bonanza (Cadiz), within the broader confines of the Coto Donana. Any one of these sites is sometimes unoccupied, but one at least always has some birds so the local population fluctuates between 150 - 550 pairs. I've also seen birds in early spring behaving as if they might nest on the Mesas de Asta marshes. For good views, though, nowhere beats the salinas at Bonanza. So this welcome increase means that it's been my good fortune to see this handsome gull regularly over the past few years and my initial impression of its distinctiveness has only increased. Adult birds with a pinkish hue can be seen at all seasons, but it's in the breeding season (April-June) that they're at their best. At this time too the red legs take on a slightly darker shade and the bill, scarlet over the winter, becomes dark almost to the point of being black. Seen at close quarters the iris can be seen to be pale straw and there's fine red rim around the eye itself. But it's the colour of the underparts that can be really striking and truly earns the species its Italian name 'Gabbiano roseo'. Some, it's true, are hardly more pink that the odd Black-headed Gulls, but others are much brighter. Fewer still are a bright day-glow pink on the head and underparts with a delicate pink suffusion invading tail, the white wedge on the forewing and even, in the most excessive examples, the pale grey back. This sets of the mascara'd bill wonderfully. Add to all this the elegantly long neck supporting the somewhat aesthetically stylish flat head and you have the image of a gull masquerading as a top Paris supermodel on the catwalk. It's all delicacy and refinement! Even one who often suffers from Laridae-phobia couldn't fail to be impressed. Then, as if that weren't enough on the water with its head held high, its giraffe neck inclined at an angle and its rear parts raised it looks like a phalarope wannabe (see Wallace's drawing from 'BB'). In short they're very handsome birds and well worth a trip to Bonanza.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed