Iberian Chiffchaff in the Alcornocales

Iberian Chiffchaff in the Alcornocales  Rear-Admiral Lynes on an African ornithological expedition in the 1930s

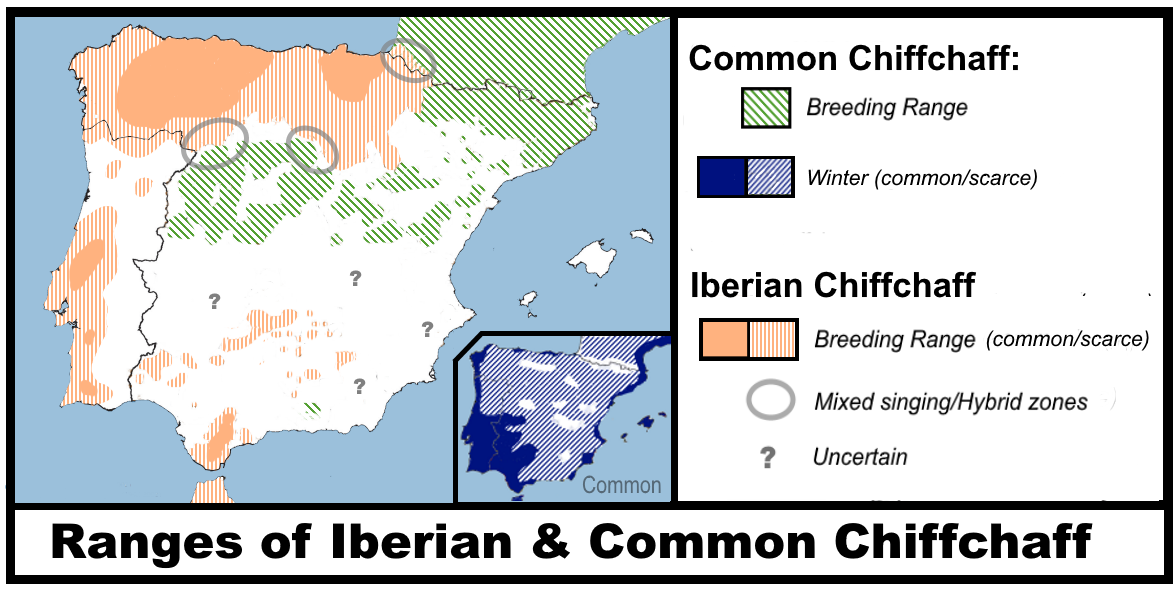

Rear-Admiral Lynes on an African ornithological expedition in the 1930s  Preliminary distribution as per Spanish Atlas 1998-2002

Preliminary distribution as per Spanish Atlas 1998-2002  Based on the Sanish Atlas, Garcia et al & other sources .... but not necessarily 100% accurate!

Based on the Sanish Atlas, Garcia et al & other sources .... but not necessarily 100% accurate!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed